beauty

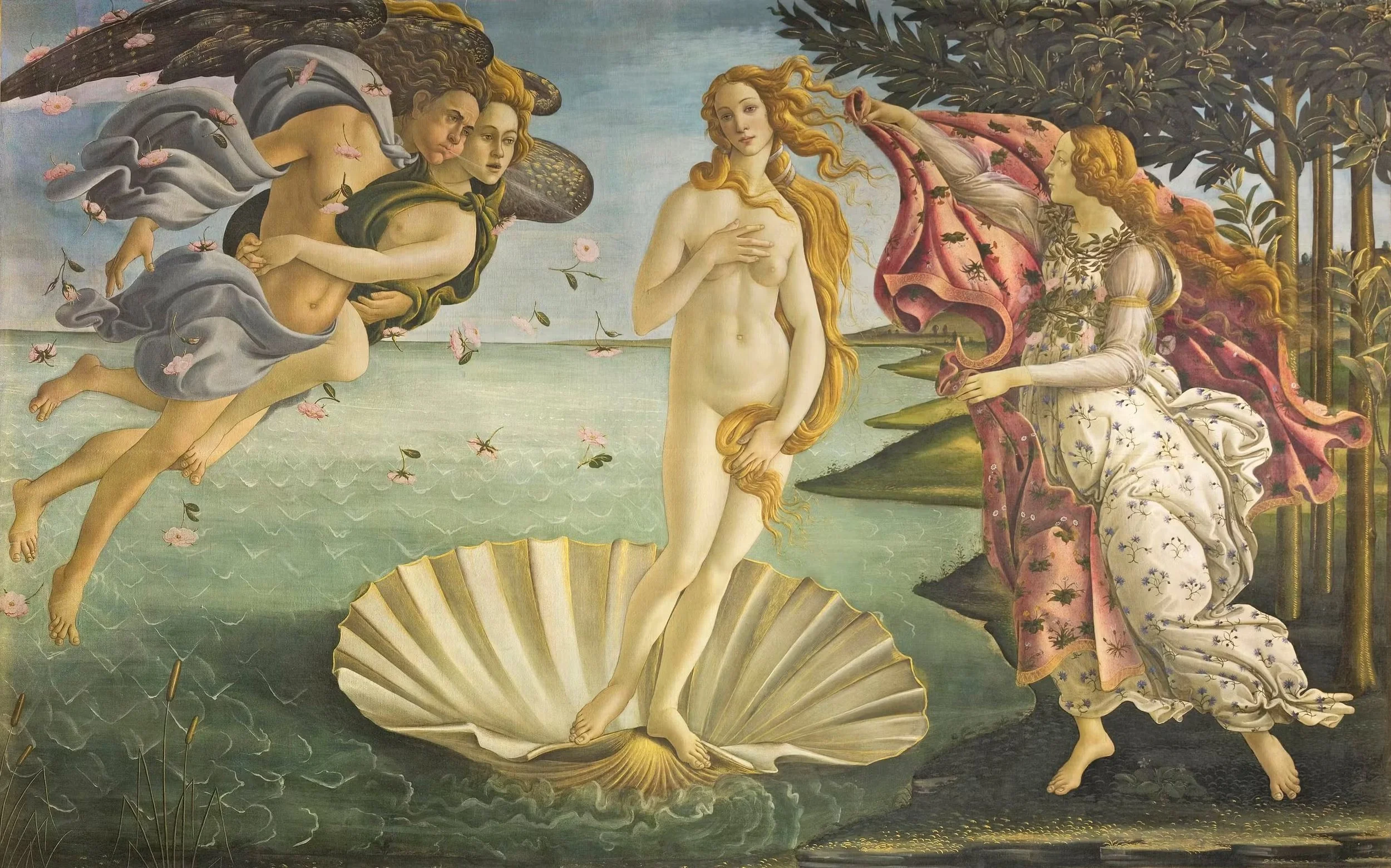

Birth of Venus - Botticelli (1485)

Personally, I don’t think art needs to be beautiful to be good

I like art that makes me feel uncomfortable maybe even more than I like art that is so aesthetically pleasing I want to hang it on my bedroom ceiling. I like art that I can’t take my eyes away from, for good or for bad. I like art that’s intoxicating. I like art that inspires ideas, triggers the imagination. I like art that I can’t get out of my head, that I’m still thinking about for days on end. Does that make it beautiful in its own way?

What is beauty, anyway? Whilst we’re here, making such overarching statements, it’s probably best to define what beauty is first. Does beauty have to incite a smile, be pleasing to the eye? Maybe all good art is beautiful, depending on your definition. I’m sorry to start this piece the way all basic best men start theirs at a wedding reception, but given its purpose, and hopeful conclusion, is a definition, the obvious place to start is the dictionary. Despite the hundreds of diverse, often contradictory, pages written on this subject over centuries by multitudes of aesthetic philosophers, all one-liners come to the same conclusion: beauty makes something pleasurable to perceive, be it to the senses, the mind, or both. Seems simple and accurate enough. Enough to confidently use it in our day-to-day lives, without fear of misinterpretation. But that’s just in English, and there’s enough variation in linguistics for me to confidently say there are many cultures with many words for beauty, each with a slightly different meaning (one for each of the senses, perhaps, and a different one completely for the mind). So, what is the purest, universal concept of beauty?

Starting with the first contradictions, all about how we experience beauty: senses vs mind; pleasure vs purpose; superfluous vs necessary; appearance vs depth.

Baumgarten, the founder of aesthetics, argues the aim of beauty is to be pleasing, to arouse desire. If something is beautiful, you feel it. If emotions are what make us human, then the ability to distinguish, and appreciate beauty, is part of what differentiates us from robots. Mario Pilo states that beauty is the product of our physical sensations; although for me here arises the question of the chicken and the egg; causation vs result: is beauty the method through which we describe and display our physical sensations, or what incites them in the first place? Did we create this concept of beauty to satiate our senses, or did the beautiful reveal our senses to us? Do our emotions dictate what is beautiful, or does beauty dictate our emotions?

Spencer would define the sources of aesthetic pleasure as (1) that which exercises the senses in the fullest way (greatest exercise with the least detriment – this lack of effort required from the receptors is a recurring theme), or depth; (2) that which gives us the greatest variety of evoked feelings; and (3) the combination of (1) and (2) with the idea they produce. I would agree that the highest form of beauty evokes both this depth and variety of senses. Spencer’s follower, Grant Allen, agrees that the beautiful is that which affords the greatest stimulation with the least expenditure.

Whilst some languages may differentiate between sensual beauty, and the beauty of knowledge, Jungmann agrees that beauty is a supersensory quality foremost, which produces pleasure in us through contemplation alone; however, he does not differentiate between that immediate reaction, and the contemplation which requires time, which is solely of the mind. On the other hand, Pictet finds beauty consists in the immediate and free, as the manifestation of the divine idea, which manifests itself in sensuous images. Hemsterhuis argues that, yes, beauty is that which gives us the greatest pleasure, but also argues that this greatest pleasure arouses from the mind; it’s that which gives us the greatest number of ideas in the shortest time; an example so beautiful it provides fast clarity to a majority. He notes the pleasure of the beautiful is the highest knowledge to which man can attain, because it provides the greatest number of perceptions. (But can the majority perceive the highest knowledge? Is beauty found in simplicity?) In other words, sensual pleasure, whilst more immediate, and provides initial enticement, is shallow, and the strongest pleasure is that of the mind. Winckelmann divides beauty into three kinds, beauty of: (1) form; (2) idea; (3) expression (which is only possible in the presence of the first two conditions). Whilst it depends on the subject, I would argue the most beautiful has both: the sensual pleasure to lure you in, and the soulful pleasure to keep you. The soulful pleasure has lasting attraction. It has purpose. As Todhunter notes: beauty is infinite attractiveness, which we perceive through both reason and love. Whilst the highest form of beauty evokes both depth and variety of the senses, it must also in turn, provoke ideas.

On the other hand, Kant claims that the source of beauty is pleasure, without practical usefulness, which appears in two facets: the subjective sense, which without concepts nor practical benefit is generally & necessarily pleasing; and the objective sense, which takes the form of a purposeful object such that it is perceived without any notion of its purpose, it is beautiful regardless of its aim. In other words, he argues that pleasure must be disparate from purpose. Beauty is superfluous, not necessary. This is in-line with Schiller, who decides that the source of beauty is pleasure without practical usefulness; in other words, play. They both note that play is not a worthless occupation in itself, but the joy it brings is a manifestation of the beauty of life. With no other aim, other than beauty. As Spencer noted, for animals other than humans, the majority of energy is spent on survival, but for us these needs have been satisfied, and there remains this surplus energy which is used in play. If Americans live to work, and Europeans work to live, living is playing. And play is often a likeness of reality, without consequence, warped through the creator’s eyes into their own vision of what they want it to be, into pure pleasure. In order for beauty to be pure, pleasure must be its sole aim (and any learning done along the way is an unnecessary byproduct). Indeed, Herbart notes that beautiful objects often express nothing at all; such as rainbows, which are beautiful due to their lines and colours (although one could easily ascribe meaning to them – the light at the end of a storm; the pot of gold at the end). So, whilst beauty can often lie within the excess, I do not believe that’s its sole habitat. Yes, it can exist without a purpose, but it can also exist due to the purpose, and the beauty in which that purpose was achieved, such as an elegant solution to a (maths) problem.

So yes, something can be beautiful and vapid, devoid of meaning; although, rightly or wrongly, meaning can be derived from beauty; but is this forcibly placed? The meaning does not create the beauty, but I would argue that it adds to it, so long as the meaning is true (or the closest to truth we can get). On the contrary, rather than seeing any semblance of beauty in the vapid, Hegel views beauty as the idea shining through matter; the manifestation of an idea (beauty comes from the meaning). Krause finds true beauty is the manifestation of an idea in individual form, refined into one simple concept. Ruge claims beauty is the idea fully expressed (whilst an unfinished idea is an imperfect expression). But is an idea only beautiful when it is complete? Does the conclusion provide 100% of the satisfaction? Or does the journey provide some (if not all) of the pleasure? Vischer sees beauty as the idea in the form of a limited manifestation. He views the world as a system of ideas, layered lowest to highest; least beautiful to most; but even the lowest levels contain beauty, as they constitute a necessary link in the system. I agree that there are different levels: whilst the highest form of beauty evokes both depth and variety of the senses, which either provokes ideas, or is prompted by them, this is the cumulation of many different sources of beauty; some of these lower forms never evolve, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t beautiful. If they aren’t the true definition of beauty, they at least have some semblance of beauty. Once again, we find the chicken and the egg: do the lower forms of beauty borrow characteristics of true beauty; or is true beauty an amalgamation of the lower forms? Are they pieces of the infinite puzzle; the higher the form, the more pieces are encompassed?

Taine doesn’t see beauty as having to be the idea, rather the essential character of ideas that are significant (I suppose what makes an idea significant is another conversation). This is more perfect than that which is expressed in reality, rather a distillation into a pure, theoretical form. Beauty is not merely the initial, shallow, satisfaction of the senses; rather in knowledge there is (power and) beauty. Solger similarly states the idea of beauty is the principal idea of any thing; the pure soul of an idea. That which feels almost untouchable by man (that’s where art comes in, making beauty accessible), for we only see the perversion of this principal idea. Beauty goes beyond mankind’s definition, beyond trends; it is instinctive, deep in your soul. In other words, lower forms borrow characteristics of true beauty, which in itself is intangible, and therefore unattainable by mortal life. All we have access to are the lower forms, guiding us to that untouchable beauty (truth?).

So now we’ve delved into the next array of contradictions, arguing the meaning behind beauty: the spectrum vs perfection; reality (limitations) vs ideals (freedoms); finite vs infinite; human creation vs divine perfection; hedonism vs morality; nurture vs nature; art vs science; practical vs theoretical. We’re back to aesthetics’ founding father, Baumgarten, who divided perfection into three: the true (logical); the good (moral); the beautiful (sensuous).

Coster concludes that ideas of the beautiful, good, and true are innate; they illuminate our reason, and are identical with God (who is goodness, truth and beauty). Hegel is convinced truth and beauty are the same: truth is the thinkable idea in itself, which, once expressed in consciousness, becomes beautiful. Is this like wearing make-up versus being fresh-faced? Whilst falsities can appear beautiful, this is deceiving, for the reality/truth (substance) is not. Is make-up merely the sensuous temptation, that provides the patience to witness the true beauty of the soul? Whilst beauty can hide (disguise) an ugly truth, William Ker argues it also gives us the means to fully comprehend the objective world, illuminating truth, clarifying and providing understanding without the need for or ability of science. Beauty is the method through which the message (of truth? knowledge?) comes.

Morley finds that beauty is found in a man’s soul; nature speaks to us of the divine, and art is the hieroglyphic expression of the divine. Similarly, Solger views art as the likeness of creation. This leads me back to another chicken and egg question: what came first, God or art? For they’re both representing truth here (but only that which is good). And so, we have ventured into religion: what do you perceive as God? I’ve delved into this concept elsewhere: ultimately, I’m agnostic. I don’t believe in organized religion (whilst acknowledging I could one day be proven incorrect - hopefully not at my death, losing Pascal’s wager). I do, however, believe in a higher power, that silently guides our every move; nature (the laws of maths and physics). For me, nature is truth, or the closest thing we have to it. Nature is the derivative of everything, it’s what we learn from. For me, the infinite truth of nature is God, is true beauty. For Schelling, beauty is the representation of the infinite within the finite; the main character of a work of art is unconscious infinity. Within that infinity lies all possible futures, all possibilities, every possible interpretation of such futures. Beauty is that untouchable infinity, and everything else, all that we have the ability to perceive, falls short. Beauty is the aim of the world, according to Ravaisson, which one could interpret as the meaning of life. He thinks the most divine and primarily the most perfect beauty contains the secret. Maths is the secret to the universe, and the more we know, the more we realise we don’t know, and so we are on a never-ending hunt, for a satisfaction we will never find, but that’s what leaves the desire behind; that’s what makes maths beautiful. Does this mean maths is the most perfect beauty?

Jouffrey thinks that beauty is the expression of the invisible by means of natural tokens which make it manifest; the visible world is the clothing by which we see beauty (the lower forms guiding us to the unattainable perfection). Lévêque finds that beauty is invisible, concealed in nature; it’s through the power of spirit which manifests ordered energy. Even Baumgarten notes that the highest manifestations of beauty are in nature. Indeed, it’s often (Batteux; Pagano) thought that art consists of imitating the beauty of nature, uniting into one the beauties scattered across nature. Hegel decides that beauty is the form in which God manifests himself, through nature (the object); and the spirit (subject). Therefore the beauty of nature is merely a reflection of the beauty proper to the spirit, as the beautiful has only spiritual content. But the spirit must manifest itself in sensuous form. Whilst the sensuous manifestation is merely an appearance, this appearance is the sole reality of the beautiful. Immediately we are back to the idea (which I believe) that everything we experience is merely an illusion. Beauty, in reality, is merely a façade, as what we perceive can never touch the real thing. We are merely human. Kant believes that man perceives: (1) nature outside himself, where he seeks the true (pure reason, knowledge); (2) himself in nature, where he seeks the good (practical reason, freedom). Just as in physics, the theory may work on a sphere in a vacuum, but that’s not practical in the real world.

Schnasse instead claims there is no beauty in the world, for nature has merely an approximation of beauty. Rather, beauty is manifested in the activity of the free, conscious of a harmony that is not in nature. But beauty is a feeling proper not only to man, as Darwin notes, but to animals as well, as we see in birds’ plumage and nests. Whilst it is true, the only perfect randomness is in nature, that does not mean no harmony is found in it. Is beauty a deeper level of harmony, a conscious one, that humanity must piece together? Does beauty have to be actively created? Is beauty found in the challenge? Or is it the human soul, love and interaction with life that brings beauty? Does something have to be perceived (as beautiful) to be beautiful? Guyau argues that beauty is not anything foreign to the object itself, not some parasitic growth on it, rather the very blossoming of that being in which it is manifest; it’s soul and essence. Schelling notes that beauty is the contemplation of things in themselves, as they are in the foundation of things. The beautiful is not produced by the artist, through their knowledge or will, but by the idea of beauty itself.

Whilst much (if not all) of the truth from nature I’ve experienced has been beautiful (Euler’s identity), I don’t think beauty is a pre-requisite for truth, nor do I think truth is a pre-requisite for beauty. Sometimes the story is more beautiful than the reality (don’t let the truth ruin a good tale). As Renouvier said, let us not be afraid to say that a truth is not beautiful. The truth is often ugly, that’s why lies (and make-up) exist. So, if beauty does not have to be true, does it have to be good?

Shaftesbury’s theory is that God is the principal beauty, and that the beautiful and good proceed from a single source. The beautiful is harmonious and proportionate; the true is beautiful and proportionate; the good is beautiful and true. Therefore the true and the good must both be beautiful, but the beautiful can be neither. Even though beauty and good are separate, he finds they still merge again into something inseparable. He claims beauty is only known by the spirit; an indefinable appreciation, much like a child’s attraction, it's instinct, before society has its chance to dictate what we appreciate. Nature not nurture; just as Hegel argued only the spirit, and all that partakes in it, is truly beautiful. Cherbuliez agrees that beauty is not a property of objects, rather an act of our soul, an illusion upon our conscious (I believe everything is an illusion). He argues that there is no absolute beauty (whilst trends and tastes change over time, surely, by definition, universal perfection doesn’t, if it exists), but we think beautiful that which we think characteristic and harmonious. I can’t help but think of Tolkien’s Silmarillion, whereby Eru creates the world using music, and evil develops out of key with the symphony.

But is there no beauty outside of perfection? Winckelmann disagrees that beauty is dependent on good, rather it is completely separate from and independent of the good. Does beauty need to have a moral basis, rather than just be pleasing to the senses, as Cousin suggests? Can pure pleasure even be moral? Is pleasure only beautiful if it’s moral, as Pilo states? Or perhaps, if beauty is not true then it must be good, and if it is not good then it must be true. A lie is only beautiful if it is used for good. Immorality is only beautiful if it is honest, producing true pleasure.

Sulzer views the aim of mankind as welfare of social life, attained through education of the moral sense, and, alternatively, beauty is that which evolves and educates this sense. This morality comes naturally, although has often been misconstrued as religious. Pagano finds that beauty merges with the good, such that beauty is the good made manifest, whilst the good is inner beauty; resulting in a perpetual cycle. Hutcheson notes that in the perception of what is beautiful, we are guided by ethical instinct, an internal sense. However, this may be contrary to the aesthetic one, therefore beauty no longer always coincides with the good, but is separate from and sometimes contradicts it. After all, so often in our modern world, beauty is the result of pain: high heels; corsets; eating disorders.

But these are also indicators of wealth: high fashion; free (gym) time; nutritionists and personal trainers. Throughout history it has been left up to the wealthy to dictate what is beautiful, or more accurately, to dictate taste, for they are the ones with the education to understand it, and the free time to enjoy it, to play, to live outside of work. If taste is the result of nurture, is beauty the result of nature? Pagano defines taste as the ability to see beauty, which itself is scattered across nature. Home similarly argues that beauty is that which is pleasant, determined only by taste. He says the basis for correct taste consists in the greatest wealth, fullness, force and diversity of impressions being contained within the strictest limits. Easy enough to argue, if you’re the one with those opportunities. Diderot agrees that the arbiter of what is beautiful should be taste, but doesn’t have the arrogance to define “correct” taste, rather decides the laws of taste are impossible to establish. Todhunter notes that as beauty depends on taste, it cannot be defined. Everyone’s spirit is different.

So, whose taste matters? Our final set of contradictions focus on the viewer: subjective vs objective; personal vs universal; diversity vs singularity; contradictions vs harmony; intuitive vs complex; passive vs active; indifference vs love. Who decides what is beautiful? Why?

Another key aspect of our humanity (other than our ability to perceive infinity / perfection) is our differences; our diverse reaction to different stimuli. Reid and Alison recognise beauty as being dependent solely on the contemplator. Bergmann notes that beauty cannot be defined objectively, for it is perceived subjectively; and the task of aesthetics is to determine what is pleasing to whom. Herbart decides that beauty does not and cannot exist in itself; what exists is our judgement, for beauty is subjective, everything is relative. He says it is necessary to find the principles of this judgement, which are related to our impressions, who and what we value. Kant describes a power of judgement (constitutes the basis of aesthetic sense; our subjective, individual taste) which forms findings without concepts, and produces pleasure without desire or practical benefit. Whilst this may occasionally be the case, I personally find it hard to receive pleasure from something, designate it beautiful, and not desire it. Or perhaps the beauty is found in the satisfaction, which has killed the desire.

Grant Allen finds that individual taste can be cultivated, as long as one trusts in the judgement of the finest nurtured and most discriminative men (those capable of the best evaluation, to shape the next generation). So, is that critics? Or those whose opinions you value, whom you want to emulate, or think are “cool”. What about listening to your heart? Do we have our own instincts, or have those been warped, “cultivated”? As we grow up, and become programmed by society, do we lose our inate taste? Does nurture gradually silence nature? Or are our instincts guiding us as to whom to listen to?

Fichte says consciousness of the beautiful arises in unlimited freedom. The world (nature) has two sides, the product of: (1) our limitation (ugly), every human body is limited, distorted, compressed and constrained; (2) our free ideal activity (beauty, which we see), inner fullness, vitality and regeneration. Therefore, the ugliness/beauty of an object depends on the point of view of the contemplator: beauty is located in the soul, not the world. It’s individual. It’s personal.

Todhunter reasons the only approximation to a universal definition of beauty is the greater cultivation of people (but what this looks like in itself is impossible to define). Taste is defined by the community. Beauty is defined by the individual. Home says beauty is determined by taste, which consists in the greatest diversity of impressions contained within the strictest limits. As more people have the freedoms previously only enjoyed by the wealthy, the closer we are to being able to define a universal consensus on taste. This is reminiscent of William James’ argument that truth happens to an idea: “True ideas are those that we can assimilate, validate, corroborate, and verify… The truth of an idea is not a stagnant property inherent in it.” Just as more people corroborate truth, so can more people corroborate beauty, in turn defining taste. Just as truth can be taken away from an idea, so can beauty. Beauty is no more stagnant than truth. It is a sign of the times.

Weisse follows a similar line of thought, noting that in the idea of truth, there lies a contradiction between the subjective and objective sides of knowledge. The singular “I” perceives the “All”. There is no such thing as fact, at least none which we can perceive, only our individual interpretations. Every moment we interact with one another we are each experiencing entirely different scenes. Weisse defines beauty as a reconciled truth, uniting into one moments of allness and oneness.

Beauty can be defined in itself; the essence consists of diversity and unity, according to Cousin. As Todhunter notes, beauty is a reconciliation of contraries. Or, as Ker puts it, art abolishes the contradiction between unity and multiplicity; law and phenomenon; subject and object; uniting them into one. It brings harmony to the out of tune. It guides the lost to the right path. It defines the indefinable, such as our emotions and senses. It’s specific to you, but also universal. It’s niche, yet diverse. It’s varied, yet unified. It’s special, yet common. It makes the oxymoron make sense. Coster states that the idea of beauty includes within itself both the unity of essence, and the diversity of component elements. Beauty comes from the order which unity introduces into the diversity of life’s manifestations.

According to Schopenhauer, abstraction from our own individuality and contemplation of one of the levels of manifestation (will objectivized in the world) will give us consciousness of beauty. Recall Hemsterhuis taught us beauty is that which gives us the greatest pleasure, because it gives us the greatest number of perceptions. We all possess the ability to perceive this idea on different levels, and therefore be liberated for a time from our person. Does this mean true beauty is objective? Or at least communal? But selectively communal? It’s not relating the art to your personal story, and seeing yourself in it, rather your ability to step out of your shoes and into others. It’s not the ability to express your heart, your will, but the will of the collective. Or discovering where your place is in that story, and how you can best serve it. Finding the bridge between the subjective and objective. How can you know you are thinking in the right direction? Once again, we find ourselves back to Baumgarten, who says beauty is defined by correspondence, mutual relations to each other and the whole. As W.A. Knight says, beauty is the union of object and subject. It is the extraction from nature of that which is proper to man, and the consciousness of oneself of that which is common to the whole of nature. Unity is derived not only from collective humanity, but also from infinite, divine nature.

Whilst Adam Müller agrees that a world in which all contradictions are harmonized is the highest beauty, he argues there are two distinct beauties: societal beauty, which attracts people, as the sun attracts planets; and individual beauty, which becomes so because they who contemplate it themselves becomes a sun that attracts beauty. This individual beauty is so desired for communality, to attract people in. Beauty is necessary for survival. Humans are social creatures, and we cannot survive on our own. We also need to procreate, and achieve immortality through our offspring. As Darwin notes, this is how beauty impacts nature. Whilst shallow beauty can draw one in, and is often required to begin the mating process, it’s once you uncover the beauty of the soul that really makes a difference. This depth is what produces love, arguably the highest form of beauty.

Love is also arguably the most personal form of beauty, that is purely subjective and not communal; although it is filled with its own oxymorons. But what comes first, beauty or love? Jungmann finds beauty is the basis of love, it’s the seed that grows. Whilst Darwin’s father, Erasmus, notes that we find beautiful that which, in our view, is connected with what we love. Love and beauty chase each other in perpetual motions, pushing new pleasures upon us.

After all that, where does it leave us? Ultimately, beauty feels like multitudes of perpetual cycles, contradictions pulling back and forth, constantly spinning around us, and without them we wouldn’t notice it. For it’s like Newton’s second law of motion, a force produces acceleration, there needs to be a change in order to feel something, otherwise it will just keep plodding along in the same direction, obliviously passing you by. If they exist separately, it is in lower forms of beauty, a barely noticeable jigsaw piece, separated from the puzzle, guiding you there, but requiring its partners to be complete, to hold your attention. Sometimes pieces get lost, and sometimes you spend too long looking at the wrong one, or trying to find the next one, but it doesn’t look how you expect it. Sometimes you put the wrong pieces together, but this instability never lasts. This puzzle never ends, for satisfaction is the death of desire. Beauty is infinite.

We experience the world via our senses. Did we create this concept of beauty to satiate our senses, or did the beautiful reveal our senses to us? The senses and the mind constitute another: that which titillates the mind can invigorate the senses, and vise versa; or neither. The senses are often perceived as the shallow, versus beauty of the mind; yet that which titillates the mind can invigorate the senses, whilst that which titillates the senses can clear a path to the mind. The most perfect beauty spins both ways.

Is there a universal perfect beauty? This intangible, unattainable concept, which everything else is merely trying to emulate. Is that what God is supposed to be? For I cannot imagine there is a single piece of art that would fit this manifestation. Or is this truth? For me, they are one and the same, nature contains the infinite truth, the answers to life’s questions, and that is God. That is what we are trying to understand, to emulate. But beauty can also be found in fantasy, in hopes and dreams and stories. It may be a lesser beauty, a warped and twisted version of the truth, artificial instead of divine, but it’s still beautiful in its own right. It still exists in infinity, somewhere, for everything has a place there. If beauty is not true then it must be good, and if it is not good then it must be true.

Within this infinite puzzle lies all possible futures, all possibilities, every possible interpretation of such futures. Just as your maths teacher taught you every book that will ever be written can be found in pi. Beauty is a representation of the infinite in the finite. Sometimes you have to bend it a little to get all your pieces to fit on the page. Infinite people will appreciate it, each seeing something different.

Human nurture has piled on top of that primal truth which guides us all. We have shaped the world in a way that we have molded truth into our own, taking it to the extremes. Whilst nature is the axioms of maths, the object, our actions have unveiled the derivatives, the subject. They were always there, as are many others, these are just the ones we have chosen to uncover. We build, and twist, and shape nature to do our bidding, and soon we forget where we started, and we have to dig it back up. You learn the axioms at university, but you learn how to multiply at five. Nurture gradually silences nature, but it’s always there, defining how we do what we do. Nature and nurture are constantly playing tug-of-war, spinning in their perpetual motion.

Depending on where we are in these motions, when we try to capture beauty, what we perceive changes. Beauty is no more stagnant than truth. The lesser beauties come and go, whilst those closest to truth hold their ground longer. We each perceive it differently, in our own orbits, but it’s when we find the overlap, that we find unity. True beauty is both personal, and universal, subjective and objective. It spins the oxymorons into harmony.